World-Renowned Child Prodigy, Violin Virtuoso & Beloved Professor

Five Decades of Violin Virtuosity

Born in Long Beach, California, on August 9, 1928, Camilla Wicks led a stellar career in the dozen years after World War Two, one of a select group whose achievements helped to advance women violinists’ prominence on the concert stage. It is worth considering that around that golden time, the likes of Heifetz, Milstein, Menuhin, Francescatti reigned supreme; veterans like Elman, Szigeti, even Kreisler and Enescu, were still active and beloved; Stern was establishing himself as a major figure, Rabin was a prodigious sensation, Oistrakh and Kogan were resoundingly breaking through the Iron Curtain.

Amidst these and many other illustrious names, Wicks was emerging as one of the great soloists on both sides of the Atlantic, upheld by many as a queen amongst her peers even before the tragic death of Ginette Neveu in 1949. At the peak of her fame she retired from the concert stage to devote herself to her family. Upon resuming her career, she remained an outstanding if intermittent performer for several more decades.

Born in Long Beach, California, on August 9, 1928, Camilla Wicks led a stellar career in the dozen years after World War Two, one of a select group whose achievements helped to advance women violinists’ prominence on the concert stage. It is worth considering that around that golden time, the likes of Heifetz, Milstein, Menuhin, Francescatti reigned supreme; veterans like Elman, Szigeti, even Kreisler and Enescu, were still active and beloved; Stern was establishing himself as a major figure, Rabin was a prodigious sensation, Oistrakh and Kogan were resoundingly breaking through the Iron Curtain.

Amidst these and many other illustrious names, Wicks was emerging as one of the great soloists on both sides of the Atlantic, upheld by many as a queen amongst her peers even before the tragic death of Ginette Neveu in 1949. At the peak of her fame she retired from the concert stage to devote herself to her family. Upon resuming her career, she remained an outstanding if intermittent performer for several more decades.

Revered by colleagues and students, Wicks made few commercial recordings besides a famed 1952 recording of the Sibelius Concerto, but the vinyl records made in her early years have long been the stuff of legends among collectors. Until recently, a handful of remastered discs have served to reveal the full scope of her artistry.

Then, in July of 2015, a release of “Camilla Wicks: Five Decades of Treasured Performances,” which spans five decades and a vast range of repertoire, finally offers the most comprehensive collection of her concert performances ever likely to be assembled. Reflecting the trajectory of a sometimes tumultuous life, it offers an in-depth insight into her evolution from captivating, devil-may-care young virtuoso to profound interpreter.

BIOGRAPHY

The Early Years

Camilla's Career

THE EARLY YEARS

A Musical Family

Wicks’s Norwegian father Ingwald was no doubt inspired by the legendary violinist Ole Bull,whom he strikingly resembled, when as a child he would steal into the woods to practice on a home-made fiddle. He developed into an excellent violinist, who later trained in Paris with Édouard Nadaud and performed at the famous Salle Gaveau. Having emigrated to America, he volunteered for military service during World War One, when an injury from carrying heavy ammunition ruined his aspirations of a major career.

Wicks’s mother, Ruby, American-born but also of Norwegian stock, journeyed alone from her small Iowa community to Germany, aged just 17, to study the piano with Xavier Scharwenka. Later, the Wicks home became an unofficial music school and little Camilla spent her earliest years listening to her father teaching. He was her first and life-long inspiration and his atmospheric miniature composition, Ode to the Desert, is included in this set.

“The atmosphere in her home was intensely musical: Camilla’s elder sister, Virginia, was a precocious songwriter and went on to become a jazz manager to the likes of Ella Fitzgerald and Dizzy Gillespie,” Nathaniel Vallois writes in “Camilla’s Choice,” .

Early Childhood

When 3 ½-year-old Camilla begged for a violin, her father gave her daily lessons and she quickly blossomed into a quintessential wunderkind. “My mother told me that [her father] would be deeply moved after giving me a lesson – I was three or four – because I’d be doing something instinctively musical. Their devotion to nurturing my talent was fed by a sense of conviction, which I felt I should fulfill,” Wicks recounts.

At her fourth birthday party she played various pieces, including a trio in which she took the first violin part, her father the second, with her mother at the piano. Later that year, she performed Vivaldi’s A minor Concerto from memory in public. She was soon playing regularly at local music and business clubs, attracting considerable interest in the local press and prophecies of a career in the footsteps of Menuhin and Ricci.

Early full-length recitals included Mendelssohn’s Concerto, the Adagio and Fugue from Bach’s G minor Solo Sonata, the first movement of Paganini’s First Concerto, Vitali Chaconne and short pieces. She made her debut with orchestra aged 7 with Mozart’s D Major Concerto K.218, at the Long Beach Municipal Auditorium. At the age of eight she performed the Bruch Concerto no.1 with the Los Angeles WAP Orchestra and Paganini’s First Concerto the following year.

A 1937 review in the Hollywood Citizen News said:

“Her tone is of amazing depth and appealing quality, her palpable quality of understanding, her poise and dignity…the child is already a fine artist, her possibilities are unlimited.”

The Julliard Years

A foundation fund was set up to enable 10-year-old Camilla to study in New York’s Julliard School with the great Louis Persinger, who had earlier taught Menuhin, Ricci and Bustabo. Until then, her father had been her main teacher, aided by Carlton Wood, a former student of Sevčik’s, who transmitted to her the solid technical foundations of the famed Bohemian pedagogue. Wicks herself equally credits her mother’s abilities on the piano and eagerness to accompany her as having been crucial in her development, learning from the start how to think of the music beyond her own part, vertically and harmonically.

“But even in the technical material, he constantly emphasized beauty of sound, color and expression. I went through the entire repertoire with him and he was instrumental in establishing me in New York. Even after I had started performing regularly, I would often go back to Persinger for coaching.”

In her later teens and on the verge of a full-blown career, Wicks would also study for about a year with Henri Temianka, whose rigorous intellectual approach contrasted Persinger’s teaching in a complementary way and honed her analytical skills.

“Temianka inspired me in a totally different way … It was a period of considerable artistic growth for me. He would ask why I did something a certain way, and I had to give solid, logical reasons. The reasoning, “I do it that way because it feels good,” was unacceptable. As a result, I developed the ability to analyze my own playing,” Camilla said.

CAMILLA'S CAREER

New York Debut

Wicks made her New York debut with a Town Hall recital in February 1942. Accompanied by Persinger, her program included Brahms’s A Major Sonata, Ysaÿe’s Ballade, Paganini’s First Concerto in Wilhelmj’s arrangement and an unusual selection of short pieces by Samazeuilh, Monasterio, Albeniz, Scott and Kompaneyetz.

In 1943, having earned an award from the Los Angeles Philharmonic Society, she made her debut with that orchestra performing Saint-Saens’s B minor Concerto. A reviewer commented:

“There is a straightforwardness about her playing that spurns sentimentality and indicates a good basis for an eventual greater profundity.”

This spurning of sentimentality combined yet with incandescent expressiveness is a hallmark of Wicks’ playing, already evident in probably the earliest existing recording of her playing, a broadcast of the Glazunov Concerto from a 1943 New York recital.

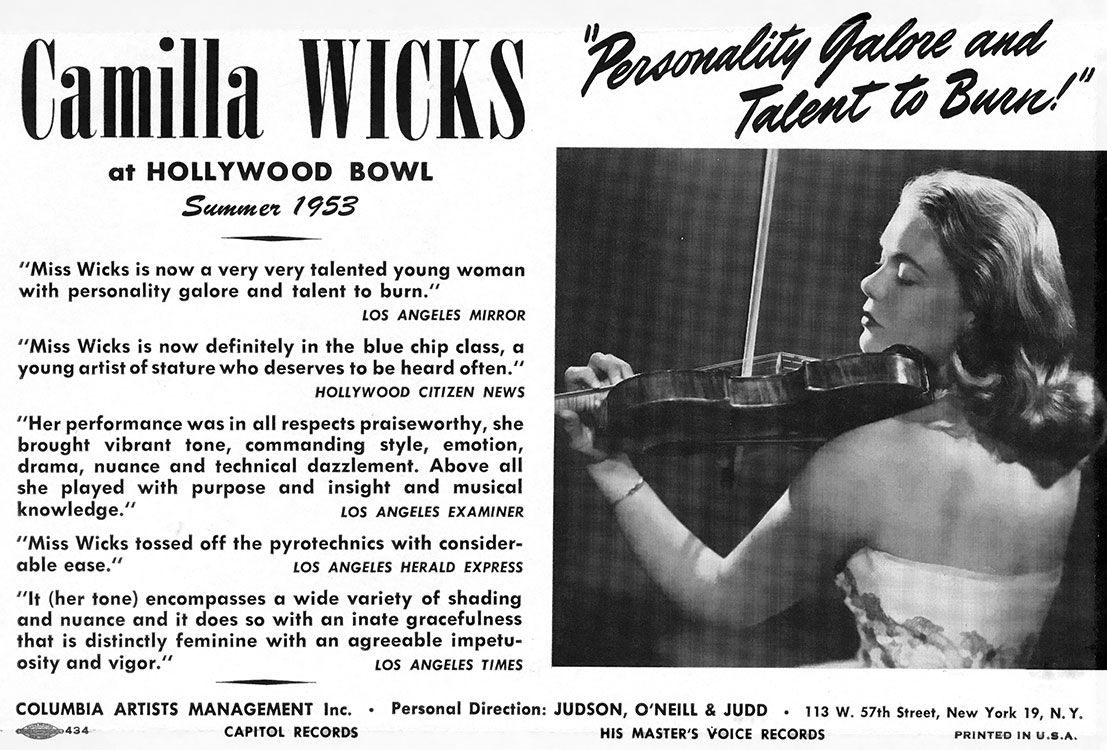

At 15, Wicks earned second prize in the prestigious Leventritt Competition, for which Zino Francescatti was one of the jurors. His warm recommendation led to her official Carnegie Hall debut, in April 1946, with the New York Philharmonic conducted by Artur Rodzinski. For this important occasion, Wicks chose the Sibelius Concerto, a work she would become strongly associated with.

An exceptionally exciting and also beautiful performer, her star quickly rose to great heights. Engagements followed with many of the leading American orchestras under such conductors as Stokowski, Reiner and Walter.

From this early phase of her career, Wicks’s swashbuckling Wieniawski D minor Concerto, from Hollywood Bowl in 1946, has a propulsive energy and incandescence that out-Heifetzes Heifetz! There are signs of tension between the barely 18-year-old Wicks and Stokowski – they did not get on – and all those decades later Wicks has come to look upon the performance with ambivalence. Yet it has an amazing sense of conviction, not to mention skill and passion.

This spurning of sentimentality combined yet with incandescent expressiveness is a hallmark of Wicks’ playing, already evident in probably the earliest existing recording of her playing, a broadcast of the Glazunov Concerto from a 1943 New York recital.

At 15, Wicks earned second prize in the prestigious Leventritt Competition, for which Zino Francescatti was one of the jurors. His warm recommendation led to her official Carnegie Hall debut, in April 1946, with the New York Philharmonic conducted by Artur Rodzinski. For this important occasion, Wicks chose the Sibelius Concerto, a work she would become strongly associated with.

An exceptionally exciting and also beautiful performer, her star quickly rose to great heights. Engagements followed with many of the leading American orchestras under such conductors as Stokowski, Reiner and Walter.

From this early phase of her career, Wicks’s swashbuckling Wieniawski D minor Concerto, from Hollywood Bowl in 1946, has a propulsive energy and incandescence that out-Heifetzes Heifetz! There are signs of tension between the barely 18-year-old Wicks and Stokowski – they did not get on – and all those decades later Wicks has come to look upon the performance with ambivalence. Yet it has an amazing sense of conviction, not to mention skill and passion.

European Tours

1946 saw the first of her European tours, when one initial engagement in Oslo turned into a total of 88 concerts over four months. Over the next decade, Wicks went on six such tours throughout Western Europe (her 1951 tour of 100 concerts in ten countries lasted eight months!)

“She points out that these were not as glamorous as they might have seemed. Schedule and travel were exhausting, fees barely covered the many expenses and rehearsal time for recitals … was limited.”

In Paris, a review in Le Spectateur from 1948 praised:

“the sensational presentation of this extraordinary young violinist who comes to us from America: an absolutely exceptional nature, an accomplished virtuoso of international class, with a poetic sonority, magnificently moving, warm and of variegated colours. Her quite masculine playing reminds one of Enesco. Her bowing is of incomparable ease. Hers is a violin that sings and stirs one, and constantly makes music. Let us intensely hope that one of our symphonic associations will invite for next season this artist, who was given a long standing ovation at the end of her recital.”

Indeed, she played the Mendelssohn Concerto in Paris in 1949, Le Monde’s reviewer noting:

“She possesses a magnificent temperament: sensitivity and lyricism are wedded with a dash, a fire, a dynamism that are irresistible. As an accomplished virtuoso she imposes herself imperiously…this young, delicate woman, is consumed by the demon of music…”

These words are an apt description of the Mendelssohn Concerto included in this set, from a Copenhagen concert conducted by Fritz Busch.

A Growing Distraction

In 1951, Wicks married, moved back to California and began having children. The Tchaikovsky Concerto from Hollywood Bowl in 1953, performed just two months after Wicks gave birth to her first child is imbued with similar qualities as the Wieniawski D minor: it is an account of exceptional bravura, ardor and flair. Wicks’ choice of encore that night, the demonic “The Troll’s Windmill,” from Bjarne Brustad’s folk-inflected Eventyr (Fairytale) Suite for solo violin, showcased at once her inclination to explore off the beaten track and her strong attachment to her Norwegian roots. Her interpretation of Grieg’s C minor Sonata reveals the umbilical connection between this music – at once proud and wild, and the land in which it is sourced.

As more babies were born, Wicks continued to tour and became a particular favorite in Scandinavia and Finland. Sibelius admired her interpretation of his concerto and she was asked to perform it for the composer’s 85th birthday celebrations, broadcast throughout Europe. Her 1952 studio recording, with her close friend Sixten Ehrling at the helm of the Stockholm Radio Symphony Orchestra, has acquired legendary status.

“Her sister recounts that Isaac Stern called her ‘the greatest violinist’, and when asked whether he meant the greatest female violinist, he said, ‘No, I mean the greatest.’”

Maintaining a close connection to the Nordic countries throughout her life, Wicks was an active advocate of contemporary Scandinavian composers. In 1949 she recorded Fartein Valen’s miniature concerto (there is also a filmed performance of this work). For a Carnegie Hall performance with the New York Philharmonic in 1957, she insisted on presenting Klaus Egge’s

Concerto. Looking back on this she commented:

“No doubt I would have had a more resounding success with the Tchaikovsky Concerto, but I saw myself as something of a crusader. You have got to feel passionately about your ideals, about the value of the music you play, and go beyond treating it merely as a vehicle for a virtuoso career.”

She later recorded the Egge, along with the Sibelius, which were her only studio recording of a large-scale work. Simax also released a live recording of Brustad’s Fourth Concerto, coupled with a memorable Walton Concerto.

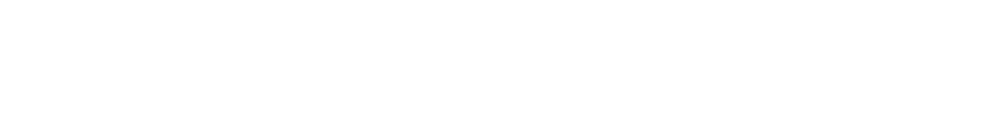

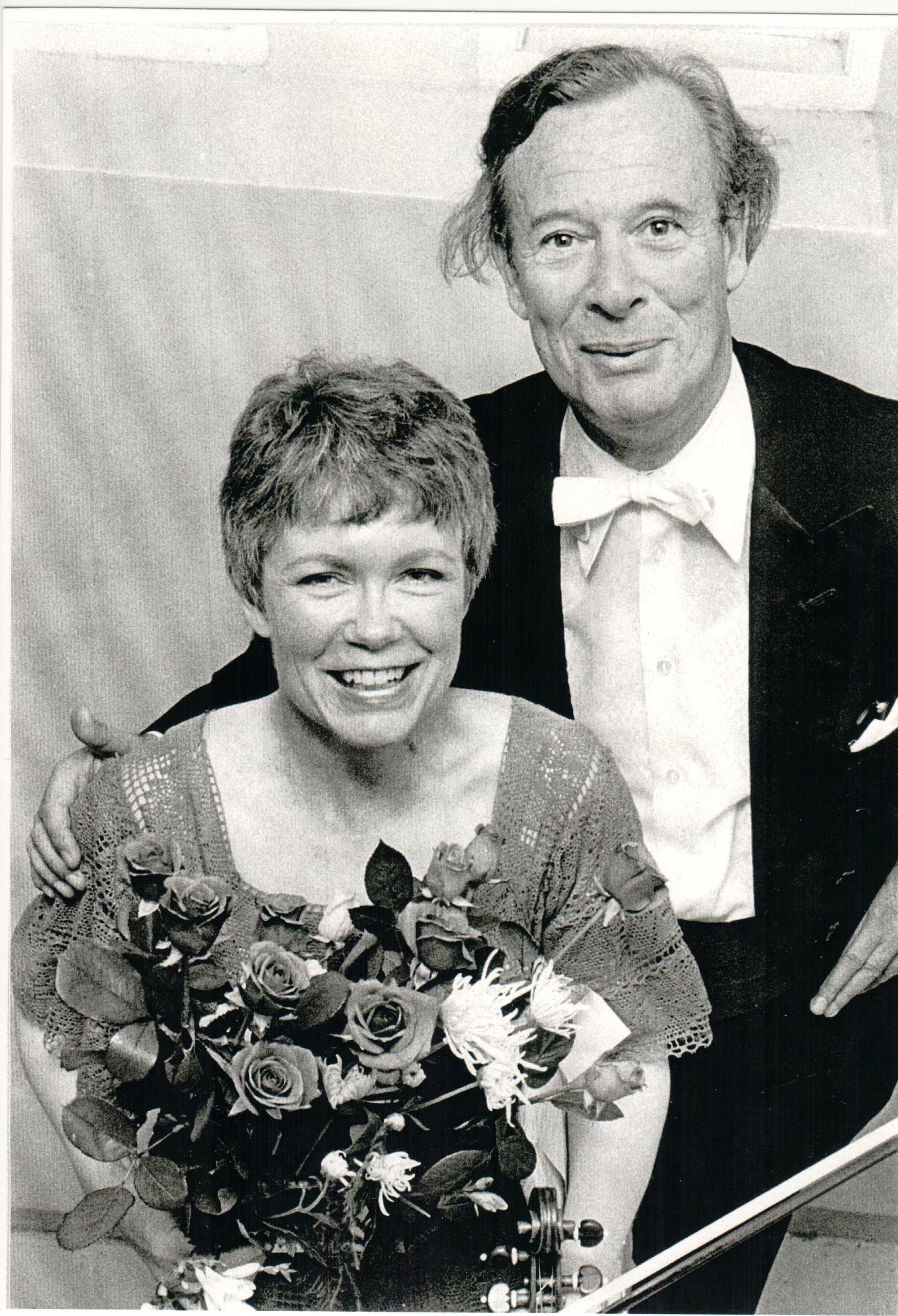

with conductor, Sixten Ehrling

As more babies were born, Wicks continued to tour and became a particular favorite in Scandinavia and Finland. Sibelius admired her interpretation of his concerto and she was asked to perform it for the composer’s 85th birthday celebrations, broadcast throughout Europe. Her 1952 studio recording, with her close friend Sixten Ehrling at the helm of the Stockholm Radio Symphony Orchestra, has acquired legendary status.

“Her sister recounts that Isaac Stern called her ‘the greatest violinist’, and when asked whether he meant the greatest female violinist, he said, ‘No, I mean the greatest.’”

Maintaining a close connection to the Nordic countries throughout her life, Wicks was an active advocate of contemporary Scandinavian composers. In 1949 she recorded Fartein Valen’s miniature concerto (there is also a filmed performance of this work). For a Carnegie Hall performance with the New York Philharmonic in 1957, she insisted on presenting Klaus Egge’s

Concerto. Looking back on this she commented:

“No doubt I would have had a more resounding success with the Tchaikovsky Concerto, but I saw myself as something of a crusader. You have got to feel passionately about your ideals, about the value of the music you play, and go beyond treating it merely as a vehicle for a virtuoso career.”

She later recorded the Egge, along with the Sibelius, which were her only studio recording of a large-scale work. Simax also released a live recording of Brustad’s Fourth Concerto, coupled with a memorable Walton Concerto.

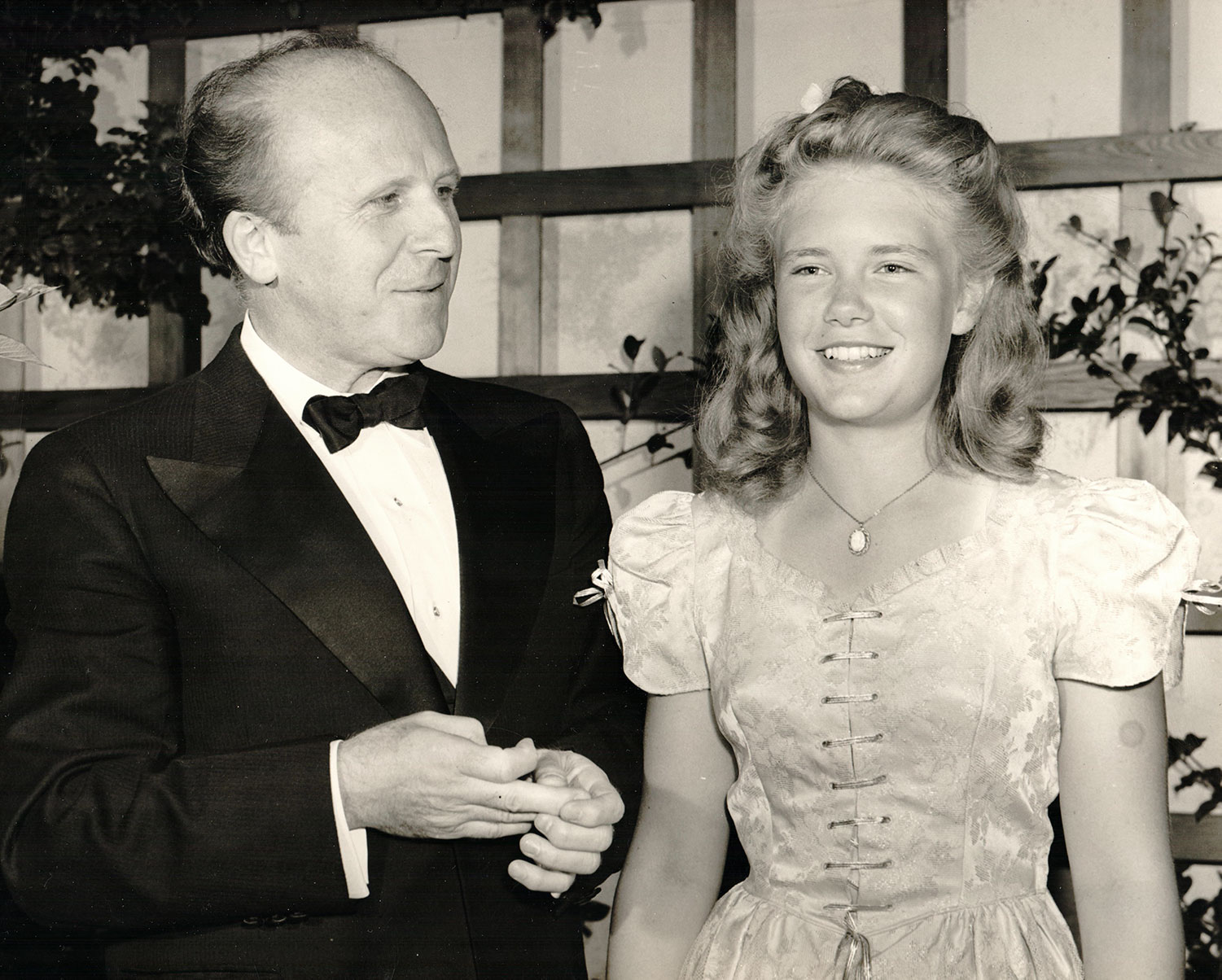

with children, Angela, Paul and Erik

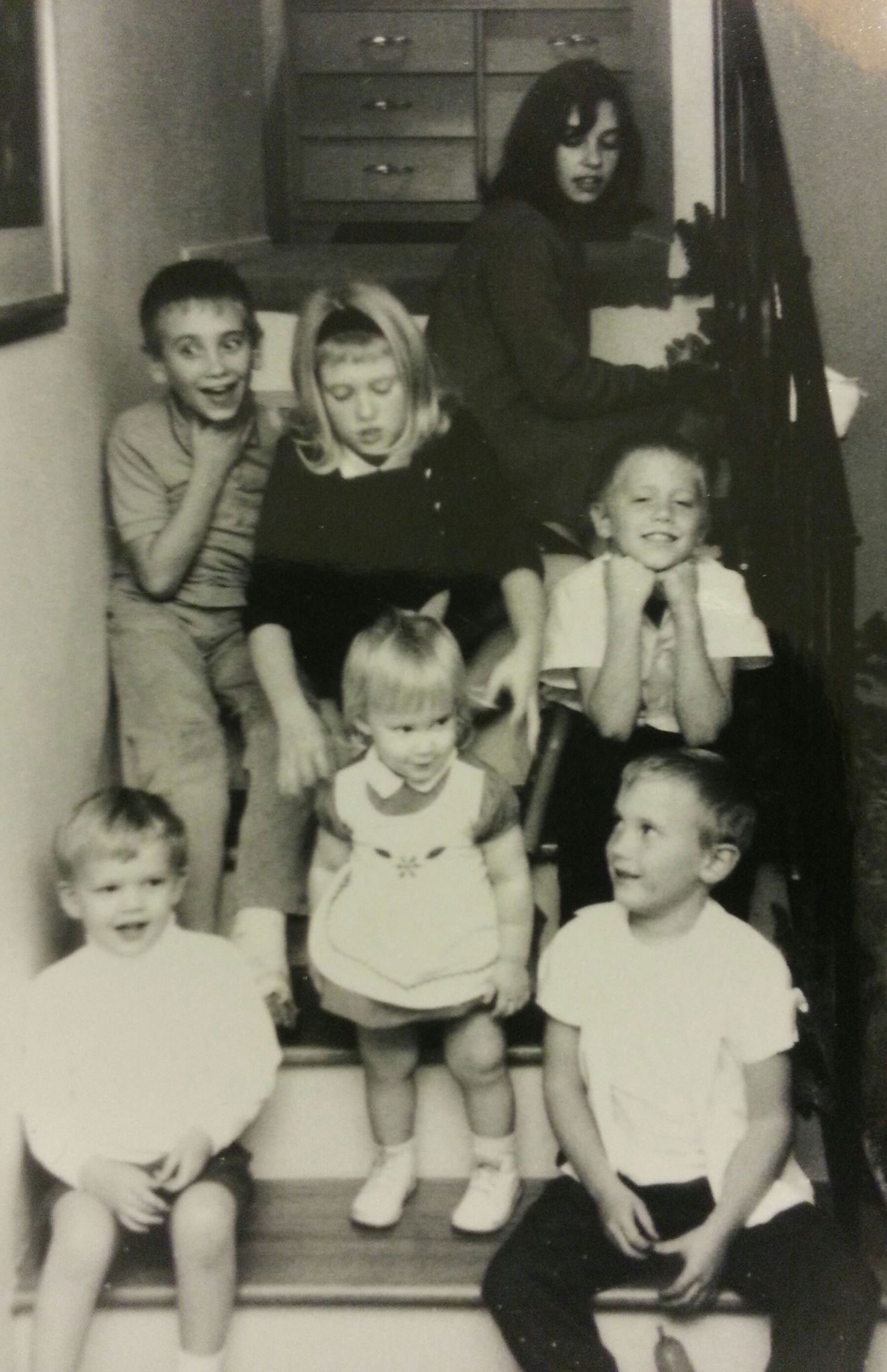

From left to right-top row, Christina (niece), middle row-Paul, Angela and Erik, bottom row-Brien (nephew), Lise-Marie and Philip

Early Retirement, Teaching and Family

From 1958 to 1966, Wicks tended to her growing family, playing concerts that were close to home. The difficulties of managing family and career began to come to a head. Her husband was asked to take a position in Texas which would require Wicks to play an active domestic role. She also accepted a teaching post at North Texas State University while concertizing as she could.

“Barely into her 30s, Wicks decided to retire. How could she have given up so much so suddenly? ‘It was not a decision taken lightly, and the memory of the efforts my parents had made also weighed upon me. But my attitude was that there’s a time for everything in life: I had enjoyed this fulfilling period of concertizing and now the time had come to devote myself to my family,’”

While in Texas, Wicks immersed herself in her husband and five children. Believing for a time that her performing days were over, Wicks even sold her 1725 Duke of Cambridge Stradivarius.

During that first period of retirement from performing, Wicks developed a reputation as a teacher. One of her early students, Jim Pettitt, recalls:

“When we began working on a Paganini Caprice or two, [Wicks] brought her copy to make some fingering notes on mine. I could see by the writing that she must have been no more than six when she put her name on the cover. It was very discouraging to an 18-year-old!”

Pettitt also recalls Wicks’ distinctive, freely tempered approach to intonation.

“She uses very subtle adjustments in pitch to clarify and emphasize key, mode, and ‘what’s next’ musically. We worked on this consciously in my lessons – my scores have little arrows up and down.”

Later, in the early 1970s, as her 14-year marriage faltered, Wicks put her growing family in the car and drove to Lake Chelan, Washington, to an area that had caught her attention years ago. Renting a house on the glacier-cut lake, the beauty, fresh air and quiet allowed her to live in semi-seclusion and make certain decisions in her life. There she taught at the Wenatchee Valley College and, typical of her, joined the small community’s non-professional orchestra.

“Nutrition became important. I gave up coffee, white sugar, cigarettes and liquor. I took pleasure being alone in the wilderness, listening to the coyotes,’” she said.

“My children have always been most important to me. They could not be five appendages to my career. Taking part in and contributing to their development, helping them through the struggles of life and witnessing the individuality of each one take shape, has been a blessing I am continuously amazed by.”

“When we began working on a Paganini Caprice or two, [Wicks] brought her copy to make some fingering notes on mine. I could see by the writing that she must have been no more than six when she put her name on the cover. It was very discouraging to an 18-year-old!”

Pettitt also recalls Wicks’ distinctive, freely tempered approach to intonation.

“She uses very subtle adjustments in pitch to clarify and emphasize key, mode, and ‘what’s next’ musically. We worked on this consciously in my lessons – my scores have little arrows up and down.”

Later, in the early 1970s, as her 14-year marriage faltered, Wicks put her growing family in the car and drove to Lake Chelan, Washington, to an area that had caught her attention years ago. Renting a house on the glacier-cut lake, the beauty, fresh air and quiet allowed her to live in semi-seclusion and make certain decisions in her life. There she taught at the Wenatchee Valley College and, typical of her, joined the small community’s non-professional orchestra.

“Nutrition became important. I gave up coffee, white sugar, cigarettes and liquor. I took pleasure being alone in the wilderness, listening to the coyotes,’” she said.

“My children have always been most important to me. They could not be five appendages to my career. Taking part in and contributing to their development, helping them through the struggles of life and witnessing the individuality of each one take shape, has been a blessing I am continuously amazed by.”

Performance, Professorship and Knighthood

When Wicks was ready to resume her performing career, her old friend Ruggiero Ricci gave her an excellent violin by the 20th Century Australian luthier Arthur Smith. (By a strange coincidence, as a small child she had played the very same half-size instrument by Klotz that had been Ricci’s a decade before.)

Her 1960 Anaheim recital, some of which is included in the “Five Decades of Treasured Performances” CD collection, was a first step towards the resumption of her performing career. Wieniawski’s fearsome F-sharp minor Concerto was a bold choice of programming and Wicks’ bravura performance suggests none of the apprehension she recalls feeling.

In the subsequent two decades, Wicks’s life and career underwent many twists and turns. Her bold character was undimmed, but an element of personal sorrow now tinged her playing.

“There was discrimination then, and I encountered skepticism towards “this pretty young blonde … Still, I don’t believe a woman can simultaneously conduct a full-blown career, sustain a successful marriage and raise a family well. She must learn to prioritize accordingly at different times of her life,” she said.

From a 1963 recital in Dallas, her reading of Chausson’s Poème – a piece she is especially fond of and describes as an “old friend” – burns with a wrenching intensity. For private reasons she took time out from performing on various occasions whilst teaching at a range of faculties: California State College at Fullerton, the Banff Centre for the Performing Arts, the University of Washington, the University of Southern California, the University of Michigan, Rice University, Louisiana State University, Eastman School of Music.

This was interspersed with a couple of years at the Royal Conservatory of Oslo and subsequent regular visits to Norway. Her contributions to Norwegian musical life were rewarded in 1999 with a Knighthood of the Norwegian Royal Order of Merit.

From a 1963 recital in Dallas, her reading of Chausson’s Poème – a piece she is especially fond of and describes as an “old friend” – burns with a wrenching intensity. For private reasons she took time out from performing on various occasions whilst teaching at a range of faculties: California State College at Fullerton, the Banff Centre for the Performing Arts, the University of Washington, the University of Southern California, the University of Michigan, Rice University, Louisiana State University, Eastman School of Music.

This was interspersed with a couple of years at the Royal Conservatory of Oslo and subsequent regular visits to Norway. Her contributions to Norwegian musical life were rewarded in 1999 with a Knighthood of the Norwegian Royal Order of Merit.

During one of her retirement stints, in the early 1970s, Wicks chose to settle with her family near Lake Chelan, in the state of Washington, in search of rural remoteness and tranquility. There she taught at the Wenatchee Valley College and, typical of her, joined the small community’s non-professional orchestra. She credits those years of quiet reflection and communion with nature as a major turning point in her life. Her last teaching position was at the San Francisco Conservatory where she held the Isaac Stern Distinguished Chair until her final retirement in 2005.

Although her essential intensity remains palpable in later performances, Wicks – always spiritually and philosophically inclined – evolved towards a more reflective approach. This emerges strongly in the slow movement of Fauré’s A Major Sonata, in Germaine Tailleferre’s marvelous yet virtually unknown Sonata, in the intimate, even mystical passages of Beethoven’s last sonata opus 96 and of Bloch’s First Sonata. Vividly imaginative phrasing within a clear-cut conception was always a hallmark of Wicks’ art. In later concerts, when the playing is sometimes slightly less polished than in her prime, the flow of inspired insights (Debussy Sonata, Ysaÿe Ballade) is unabated and the nobility of spirit (Brahms Concerto) unshakable.

Wicks’ avid curiosity always led her to championing neglected jewels of the repertoire well beyond the Nordic realm. Already in the earlier years of her career her recitals had included rarely played works by Milhaud, Honegger, Villa-Lobos, Dohnanyi, Bloch.

A later discovery of Wicks’, Tailleferre’s Sonata is highly original, rich in content and atmosphere – no doubt the most significant revelation of this collection in terms of repertoire. Ravel’s one-movement early Sonata (1897), opus posthumous, has been revived of late but still lay in oblivion when Wicks played it in the 1980s. Joaquin Nin’s Spanish Songs arranged by Kochanski, also deserve special mention. They extract the earthy, emotional and spiritual strands of Spanish popular music with captivating immediacy – far more so than Sarasate’s pieces, delightful as these are, and even than De Falla’s Suite Populaire Espagnole.

with Norwegian Hardingfele

Through her father, Wicks imbibed the earthy spirit of the Norwegian hardanger fiddler and she translated this into a visceral grasp of a myriad other folk and popular styles. Abundantly and eclectically represented here, the miniature genre showcases this striking aspect of Wicks’ art, fueled by her extraordinary sense of rhythm. Whether spinning the filigree arabesques and exalting the poignant melodious magic of the Chopin Nocturnes, shaping Paradies’ wistful Sicilienne with graceful simplicity or igniting the fiery spirit of various folk idioms, Wicks inhabits these contrasting worlds deeply and brings them to life with exhilarating flair. She becomes a ferociously guttural Flamenco cantaore (with fantastic guitar-like pizzicato in Nin’s Granadina), a soulfully eloquent Jewish Chazzan (Bloch), a sensuous Latin dancer (Sarasate, Benjamin), a Magyar or Balkan fiddler ever connected to the sounds of Nature (Bartók, Scarlatescu, Brahms, Ravel)… And from her native America, at the heart of the sizzling Gershwin Preludes, Wicks’ performance of the lyrical second is that of a great Blues singer.

The bulk of the recordings presented in “Camilla Wicks: Five Decades of Treasured Performances,” lay for many years neglected either in the vaults of radio archives or in Wicks’ own home. It was often a painstaking task to find and restore them, and sometimes it took some persuasion to convince Wicks that they formed a precious legacy! The many messages of encouragement from her colleagues, students and aficionados were a strong impulse to bring this project to fruition. It is a joy to make these great performances available – for those who have long wished for Wicks’ discography to be expanded, and to enable a wider audience to be stirred by this extraordinary violinist and artist.

Through her father, Wicks imbibed the earthy spirit of the Norwegian hardanger fiddler and she translated this into a visceral grasp of a myriad other folk and popular styles. Abundantly and eclectically represented here, the miniature genre showcases this striking aspect of Wicks’ art, fueled by her extraordinary sense of rhythm. Whether spinning the filigree arabesques and exalting the poignant melodious magic of the Chopin Nocturnes, shaping Paradies’ wistful Sicilienne with graceful simplicity or igniting the fiery spirit of various folk idioms, Wicks inhabits these contrasting worlds deeply and brings them to life with exhilarating flair. She becomes a ferociously guttural Flamenco cantaore (with fantastic guitar-like pizzicato in Nin’s Granadina), a soulfully eloquent Jewish Chazzan (Bloch), a sensuous Latin dancer (Sarasate, Benjamin), a Magyar or Balkan fiddler ever connected to the sounds of Nature (Bartók, Scarlatescu, Brahms, Ravel)… And from her native America, at the heart of the sizzling Gershwin Preludes, Wicks’ performance of the lyrical second is that of a great Blues singer.

The bulk of the recordings presented in “Camilla Wicks: Five Decades of Treasured Performances,” lay for many years neglected either in the vaults of radio archives or in Wicks’ own home. It was often a painstaking task to find and restore them, and sometimes it took some persuasion to convince Wicks that they formed a precious legacy! The many messages of encouragement from her colleagues, students and aficionados were a strong impulse to bring this project to fruition. It is a joy to make these great performances available – for those who have long wished for Wicks’ discography to be expanded, and to enable a wider audience to be stirred by this extraordinary violinist and artist.