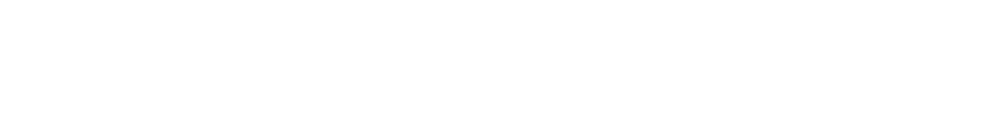

Discography

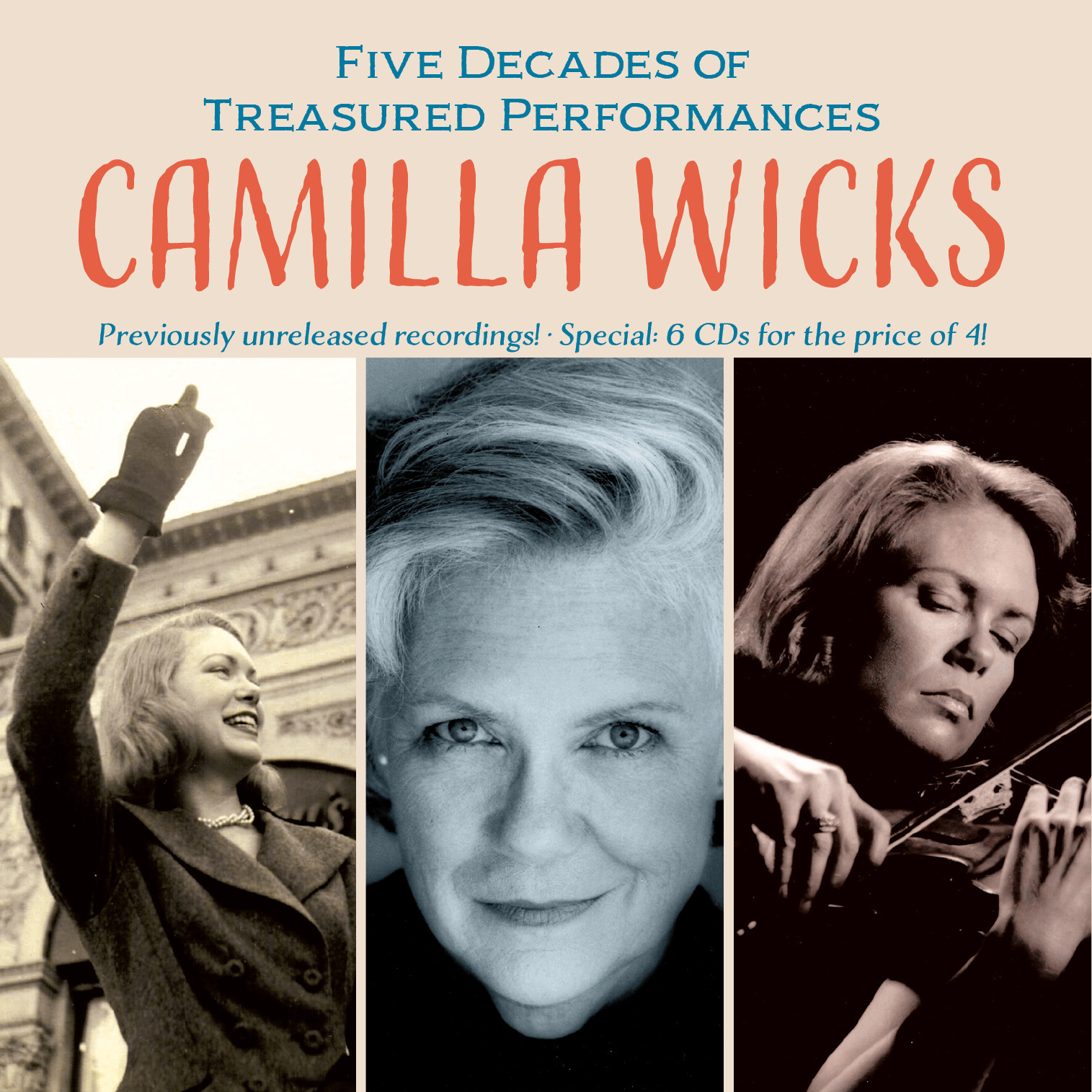

Music & Arts Presents "Camilla Wicks: Five Decades of Treasured Performances," 2015

Special thanks to producer Nathaniel Vallois, who has gathered the broadest collection of performances by Miss Wicks and packaged them in this wonderful collection of CDs. Vallois also authored the liner notes which are used throughout this website. Thanks also to co-producer and audio restoration engineer Ward Marston and audio editor Aaron Z. Snyder.

Fanfare

The Magazine for Serious Record Collectors

By Henry Fogel, Nov/Dec 2015

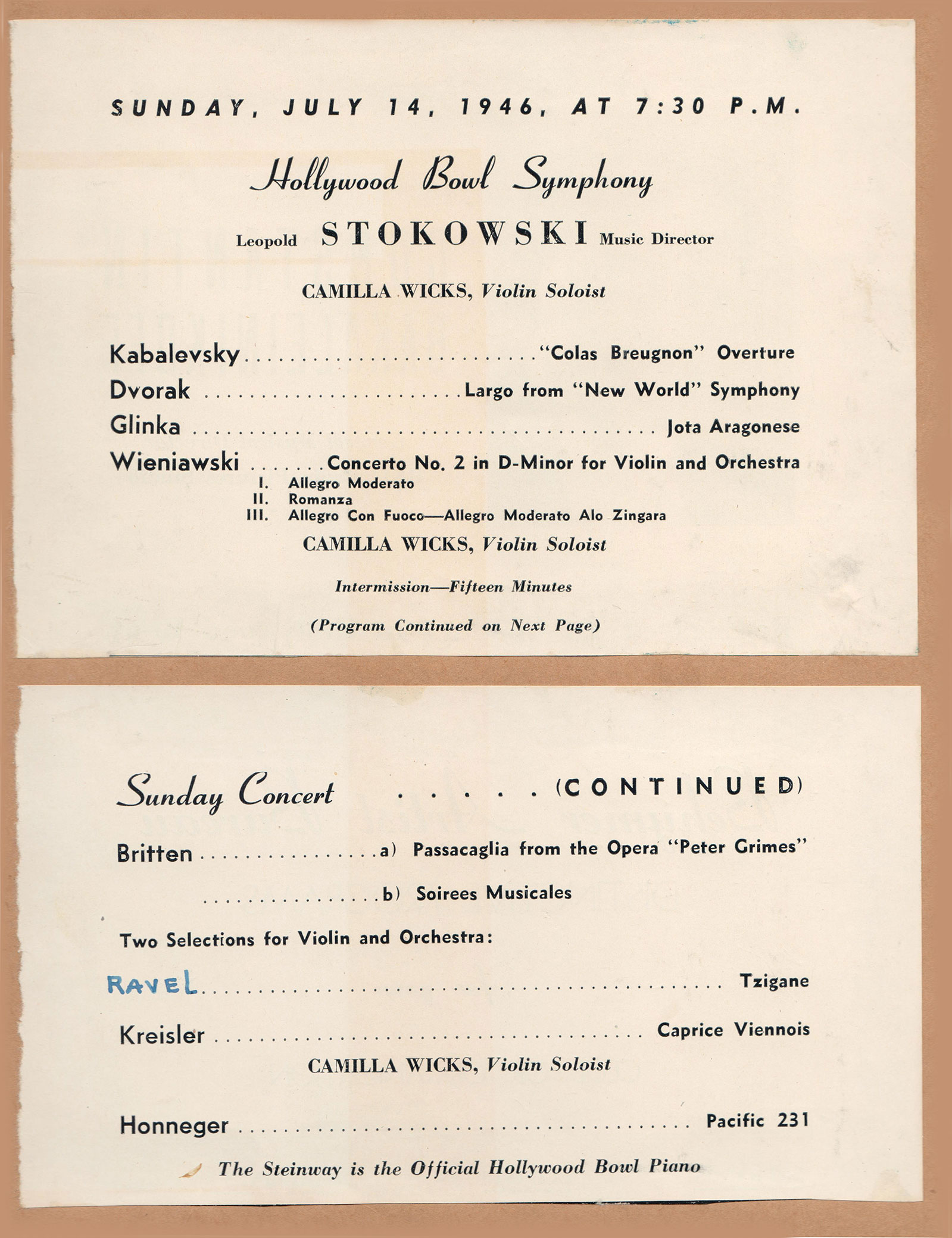

… “What is revealed in this comprehensive survey of Wicks’ career is a front rank artist who merits a greater public reputation than was granted her. Her technique is as close to flawless as humans get, and her intelligence and interpretive breadth are clearly those of a major artist. Early in her career she may well have focused on her virtuosity—the 1946 Hollywood Bowl performance of Wieniawski’s Second Concerto finds her occasionally leaving even the alert Stokowski behind (the excellent notes indicate that Wicks and Stokowski did not get along). Nonetheless, her brilliance in the finale of the Concerto is thrilling to experience. Wicks’ sound is a focused tone, without the plushness of an Oistrakh; it is perhaps closer in sound to someone like Szigeti. She does use a wide range of color and vibrato for expressive purposes…

As she matured, her approach to music became more reflective, and the correspondence from Ernest Bloch that is reproduced in the accompanying booklet reveals the enormous respect he had for her. It is a shame that although she learned the Bloch Concerto, she never performed it. But she believed that the First Sonata was the greater work, and the performance here, with very sensitive and alert accompanying from Roslyn Frantz, leaves a major impression on the listener. Wicks is utterly committed to the score, and plays as if possessed …

By Stephen Greenback, August 2015

RECORDING OF THE MONTH

“Camilla Wicks was one of a group of elite female violinists who forged distinguished careers in the mid to late twentieth century. The names of Ginette Neveu, Johanna Martzy, Ida Haendel and Erica Morini are four others that immediately spring to mind …”

… “This important tranche of material derives from both the vaults of radio archives and Wicks’ own collection. Her discography is relatively small, amounting to a single CD from Music and Arts containing live performances of the Beethoven and Sibelius Concertos, a couple of CDs on the Norwegian Simax label (review ~ review) and a Biddulph CD. This welcome box set redresses the balance by considerably expanding her discography. Whilst standard fare constitutes a large proportion, the inclusion of less well-known composers is a positive bonus …”

… “There’s no doubt, listening to the evidence, that Wicks had a stunning technique and gives impressive accounts of the nineteenth century virtuoso violin concertos and showpieces, of which there are many fine examples here. Both Wieniawski Concertos are included. No. 2, from the Hollywood Bowl with Leopold Stokowski dates from 1948. The Romance is fervent, and the third movement has a quicksilver audacity and sparkle, certainly giving Heifetz a run for his money. The First Concerto has always been my favourite of the two, though it is less frequently performed and recorded. Michael Rabin made a magnificent recording of it. Wicks is accompanied on the piano by Horace Martinez, and the concerto is a splendid vehicle for showcasing her phenomenal violinistic arsenal. Equally dazzling is Sarasate’s Introduction and Tarantelle, with orchestra, where there’s some crisply articulated spiccato passages…”

Audiophile Audition

By Gary Lemco, June 2015

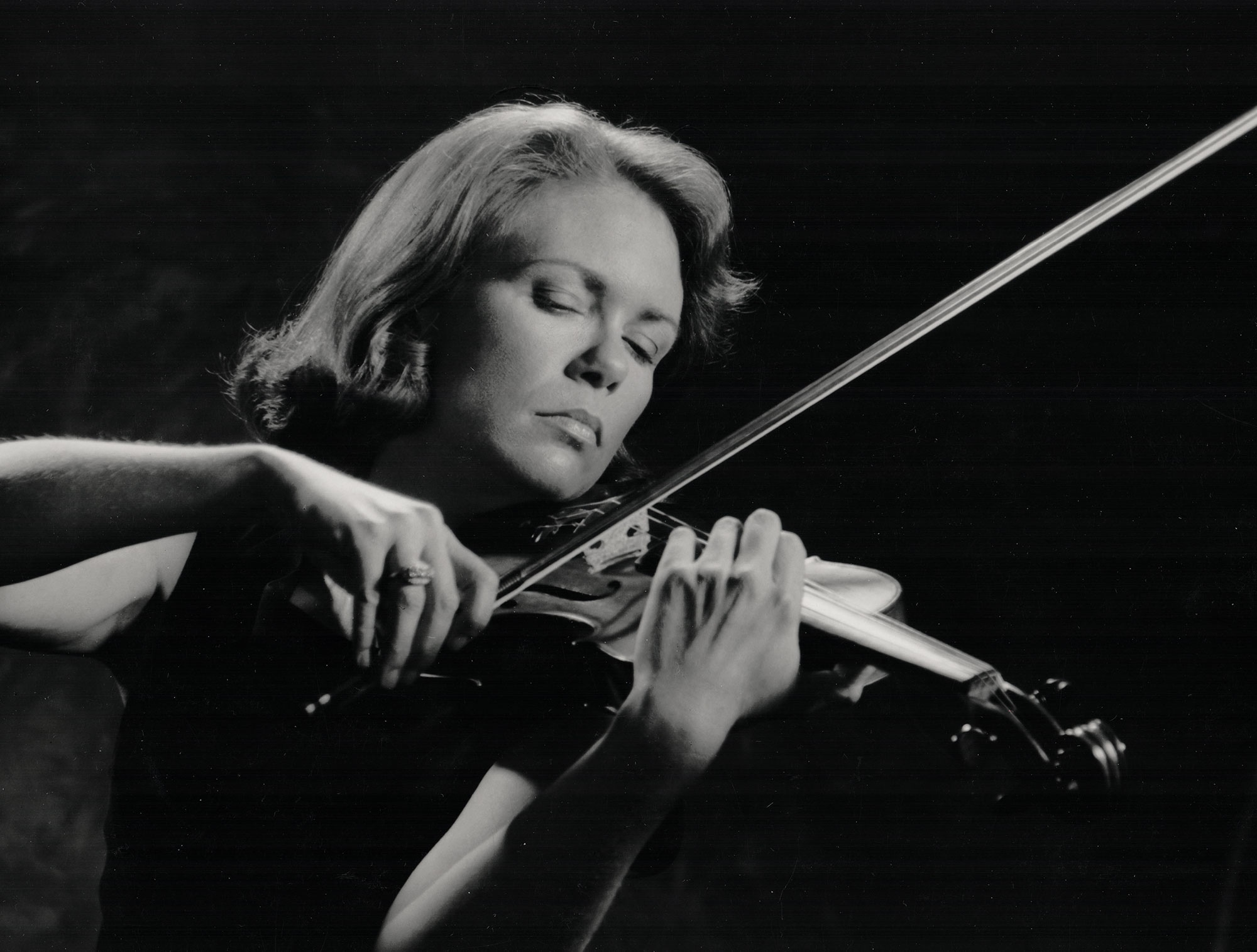

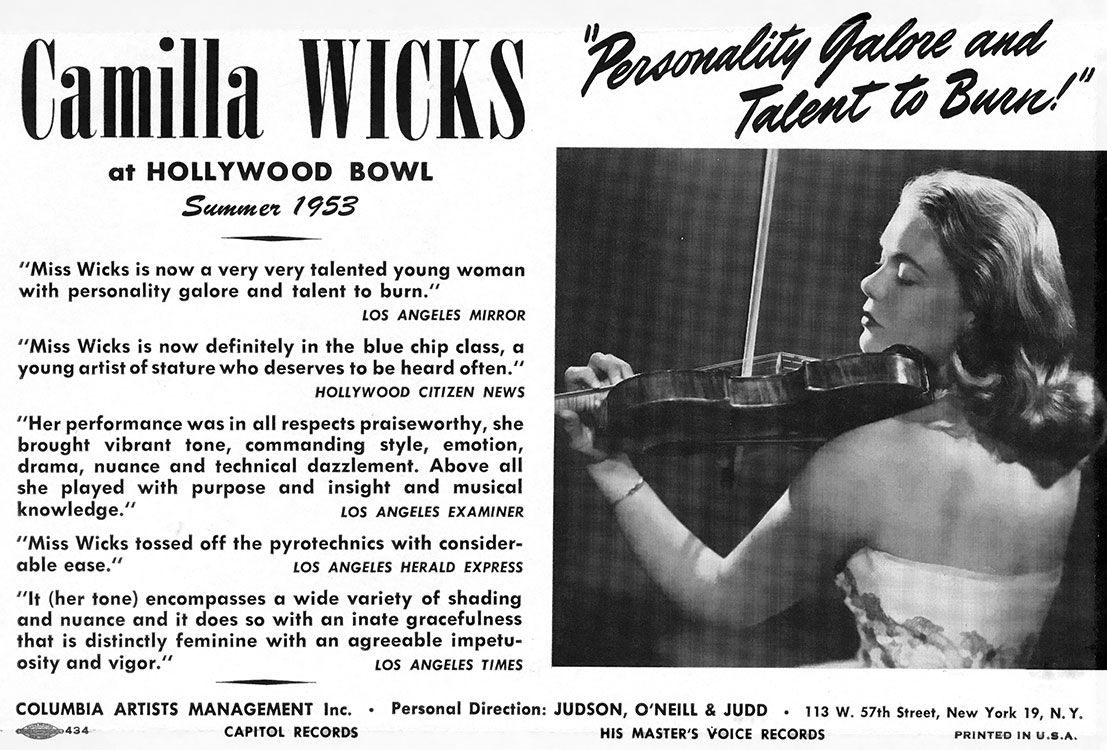

“Upheld by many as a regal presence amongst her peers, violinist Camilla Wicks (b. 1928) cultivated a stellar career in the dozen years following World War II. At the peak of her fame she retired from the concert stage to devote herself to her family. Upon resuming her career, she remained an outstanding if intermittent performer for several more decades. Wicks made few commercial recordings besides a famed 1952 performance of the Sibelius Concerto (on Biddulph 80218-2) …”

… “Perhaps the most natural place to begin lies in her performance of her “patented” Concerto in A Minor, Op. 14 by Samuel Barber, once more in (unspecified date) collaboration with Sixten Ehrling and the Radio Stockholm Symphony. Wicks provides a virile combination of lyricism and muscular drive, and the orchestral support from Ehrling bears his broad, fiery imprimatur. The American, neo-Romantic sensibility of the Concerto retains its integrity, while the obvious sympathy of the performers saturates every measure. Wicks literally consumes the difficulties of the last movement with unbuttoned relish…”

… “An originally cold-climate composer, the Swiss Ernest Bloch, befriended Camilla Wicks – much as he had violin leader Sidney Griller – whom he had met through the intermediary Louis Persinger, who had encouraged Wicks to master the Baal Shem Suite’s Nigun. The composer himself complimented Wicks on her Nigun and upon the Sibelius Concerto, which he praised for its “color without any false sentimentality.” The recorded performance of Bloch’s Sonata No. 1 (Fullerton, 1980) with Roslyn Frantz will bear fruitful comparison with any of the work in Bloch committed to record by Heifetz, Milstein, Gingold and other select artists of refined taste and immaculate technique …”

Camilla Wicks and Ernest Bloch

By Nathanial Vallois, January 2015

“… Wicks’ first contact with Bloch’s music was through her teacher, Louis Persinger (1887-1966), whom she credits as her major influence. Persinger, like Bloch himself, studied the violin with Eugene Ysaÿe, and the two knew each other well as musical colleagues in San Francisco in the mid-to-late 1920s. In that period Bloch had been inspired to compose a short piece, Abodah, for young Menuhin, Persinger’s first and most famous wunderkind student. It was the first piece dedicated to him, and he recorded it in 1939.

Persinger introduced Wicks to Bloch’s music through the Baal Shem Suite, which includes the famous Nigun. Young Camilla had no direct reference points to draw from her own background, but Persinger enlightened and inspired her to grasp its unique language. ‘Persinger didn’t talk so much about the background as inspire by his playing at the piano – by his conjuring of imagery. I still remember the way he stretched certain chords to create a tense, extraordinary atmosphere in the opening of Nigun.’

As her reputation as a formidable talent rose in the post war years, Wicks made regular broadcasts for the Standard Oil radio programme. On 28th May 1950, one such performance included the finale of the Sibelius Concerto – a work which she became especially associated with – and Nigun.

Surprisingly, Bloch had never heard his composition in its orchestrated form until he fortuitously caught this searing performance on the radio. Blazing with cantorial oratory power and heartfelt intensity, Wicks account (which was included on a Music & Arts disc, The Art of Camilla Wicks) inspired Bloch to write to her the following lines:

29 May 1950

Dear Miss Wicks,

It was by mere chance that I noticed, yesterday, that my “NIGUN” was to be performed at the Standard Hour, with orchestra. Though these pieces were instrumented eleven years ago, I have never heard them, thus far, with orchestra … I must confess, I was not without misgivings…as my works are so often misrepresented by those who have not contacted me. […] I was surprised to hear a truly great violinist interpret my work with such comprehension and musicality. […] your Sibelius! … I have no words to express my admiration. Both my wife, who is very critical, and myself were thrilled by your extraordinary rendition of this exceedingly difficult work. Everything came out superbly, easily, as if there were no technical problems … Your astonishing rhythm, colour, expression, without any false sentimentalism, constant musicality … perfect understanding of the structure. It was a joy to hear such masterly performance. And I wondered … because there was so much youth and, at the same time, such maturity. Music, and interpretation of music, are, for me, an ideal graphology; they do not lie and, through them, one can recognize the complete personality of an artist. Yours must be an exceptional one.

It is the first time, since many, many years, that I write to an artist or interpreter … But I had to. I wonder whether you are acquainted with my other, more important works, for violin: The Sonatas, Violin Concerto? You would be an ideal interpreter of them …’”

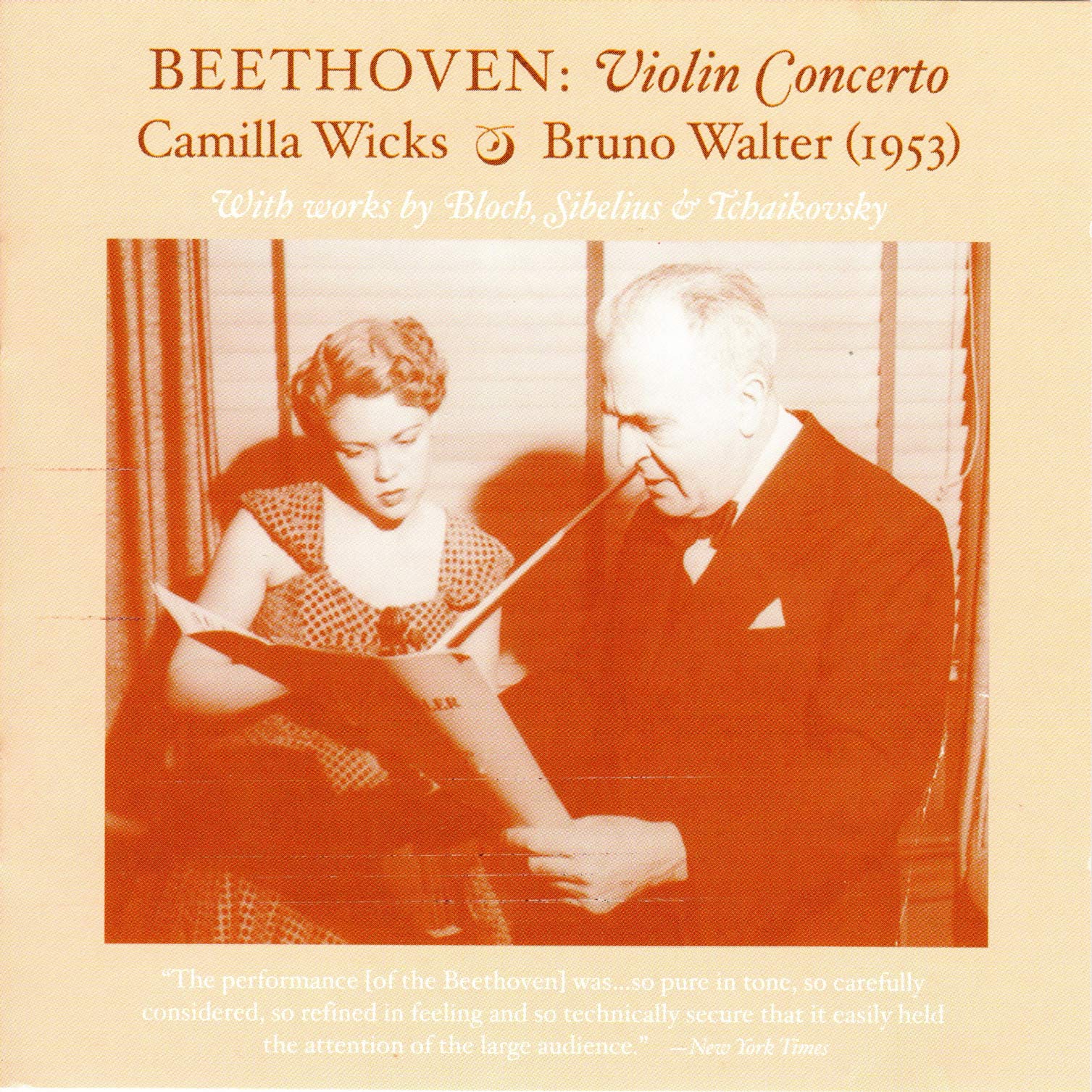

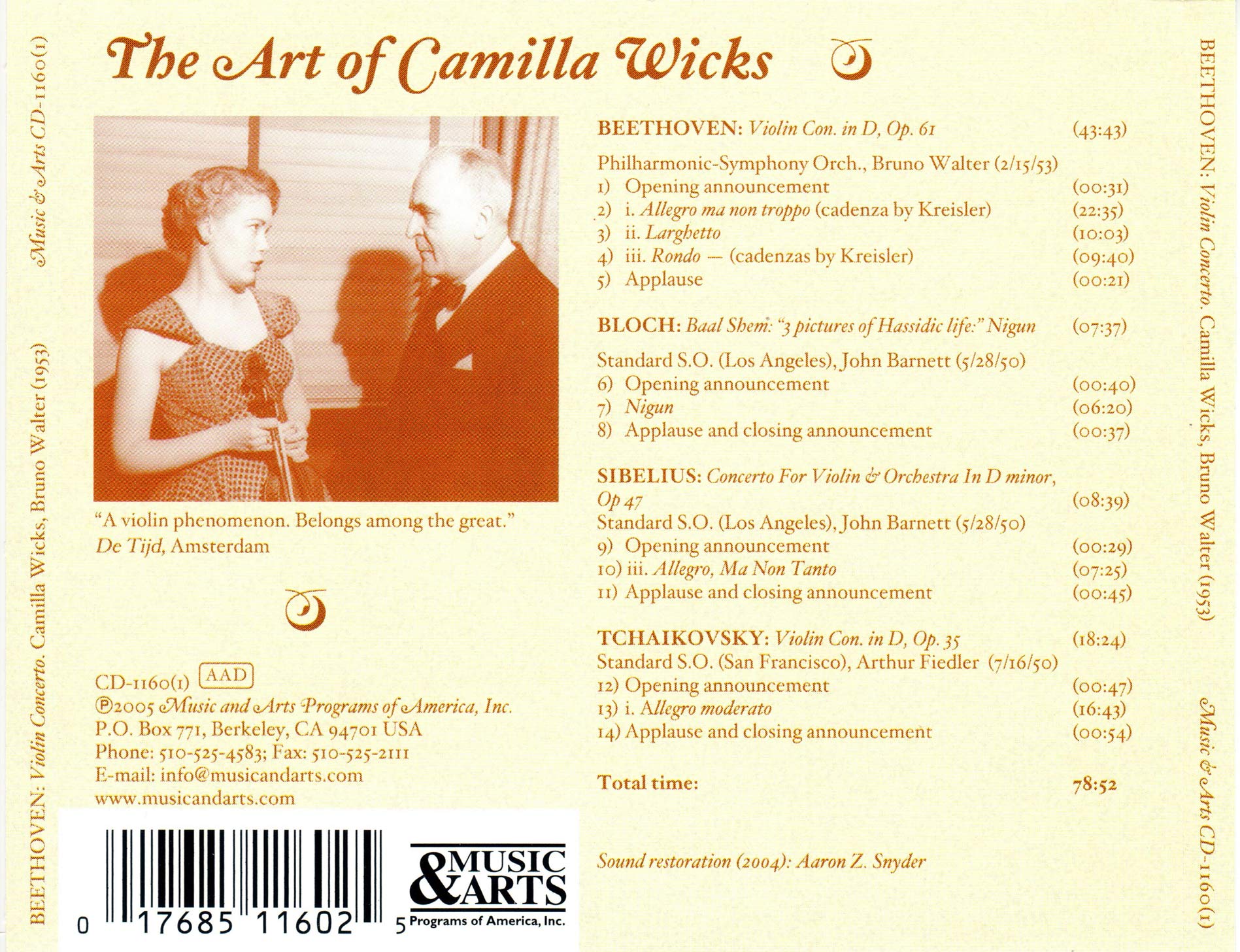

Presents, “The Art of Camilla Wicks,” 2005

- Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 61 1

- Ernest Bloch: Nigun from “Baal Shem” 2

- Jean Sibelius: Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 47 (third movement only) 2

- Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 35 (first movement only) 3

1 Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra/Bruno Walter

2 Standard Symphony Orchestra, Los Angeles/John Barnett

3 Standard Symphony Orchestra, San Francisco/Arthur Fiedler

Music & Arts CD-1160(1) AAD monaural 78:52

By Raymond Tuttle, 2005

“Because she made relatively few commercial recordings, not many remember Camilla Wicks today. (Also, it is easy for violin-fanciers to be distracted by the likes of Jascha Heifetz, Nathan Milstein, Yehudi Menuhin, and Zino Francescatti.) This new release, derived from radio broadcasts in 1950 and 1953, supports the claim that she was worthy of being mentioned in the same breath as the aforementioned male colleagues …”

… “The Beethoven concerto, played with conductor Bruno Walter in New York City (I am guessing) on February 15, 1953, receives a glorious performance. (Apparently Wicks was visibly pregnant at the time!) She plays with entirely appropriate classical purity and attention to both form and tone. If a Greek goddess could play the violin, it would sound like this. (She plays the Kreisler cadenzas in the first and third movements.) In 1953, Walter’s conducting was not nearly as cozy as it would become in the following decade, when he made his series of “Indian summer” recordings with the so-called Columbia Symphony Orchestra. In fact, Walter is surprisingly volatile here, although never outside of reasonable stylistic bounds. Together, they make “beautiful music,” as the cliché goes. This is one of the best performances of the Beethoven I’ve ever heard …”

Audiophile Audition

By Gary Lemco, 2005

… “In her early teens, Wicks was already a seasoned artist, capable of playing the Saint-Saens B Minor Concerto and the Glazounov A

Minor with efficiency and polish. By 1942, Wicks made her lifelong association with the Sibelius Concerto, whose recording in 1952 with Sixten Ehrling was destined to become a classic collectors’ item. “Mr. Ehrling was wonderful,” offered Wicks. “Some had criticized him as being intolerant and authoritarian, but I felt he simply would not put up with shoddy musicianship. He knew what he wanted. The performance is being reissued, with its pitch distortions adjusted. Ehrling was recording the Sibelius symphonies in the hall; and in the course of the day, the acoustic would shift, and my notes came out somewhat flat …”

… “The Tchaikovsky movement has a taut incandescence, keeping one slightly off balance emotionally with the dazzling fioritura of the display and uncanny, quick finger work. Her high flute-tone can be quite effective, even eerie, as it is in the Sibelius excerpt. No less intriguing to collectors should be the Simax issue (PSC 1185) of live concerts (1968, 1985) of the Walton Concerto and Brustad Fourth Concerto, the latter with Herbert Blomstedt. I asked Wicks about her 1946 performance of the Wieniawski D Minor Concerto with Leopold Stokowski. “A company wanted to issue this collaboration, but I refused to permit it. Stokowski either could not, or would not, meet my tempo for the last movement and the result was too sloppy for my taste.”

By James Leonard, 2005

“Camilla Wicks had it all — a blazing technique, a radiant tone plus a compelling interpretive point of view, and, on top of that, she was a California blonde — when she retired. Pregnant when she made her 1953 Carnegie Hall debut performing Beethoven‘s Violin Concerto with Bruno Walter leading the Philharmonic Symphony, Wicks stopped playing to raise a family of five children.

As this recording shows, at the time Wicks was at the peak of her prodigious abilities: her command, her control, her power, her passion her clear, shining tone are all gloriously in evidence. Walter was clearly charmed by Wicks and he leads the Philharmonic in an accompaniment of the utmost poise and gentility. The two performances from three years earlier — radio broadcasts of the finale of Sibelius‘ Concerto and the opening movement of Tchaikovsky‘s Concerto — are equally fine and show what a daredevil virtuoso Wicks could be. Best of all is Wicks‘ performance of Bloch‘s Nigun, an astoundingly accomplished and astonishingly reckless performance. Music & Arts’ transfer is likewise as good as it could be and reveals Wicks at her best. Anyone who loves great violin playing will enjoy this disc.”

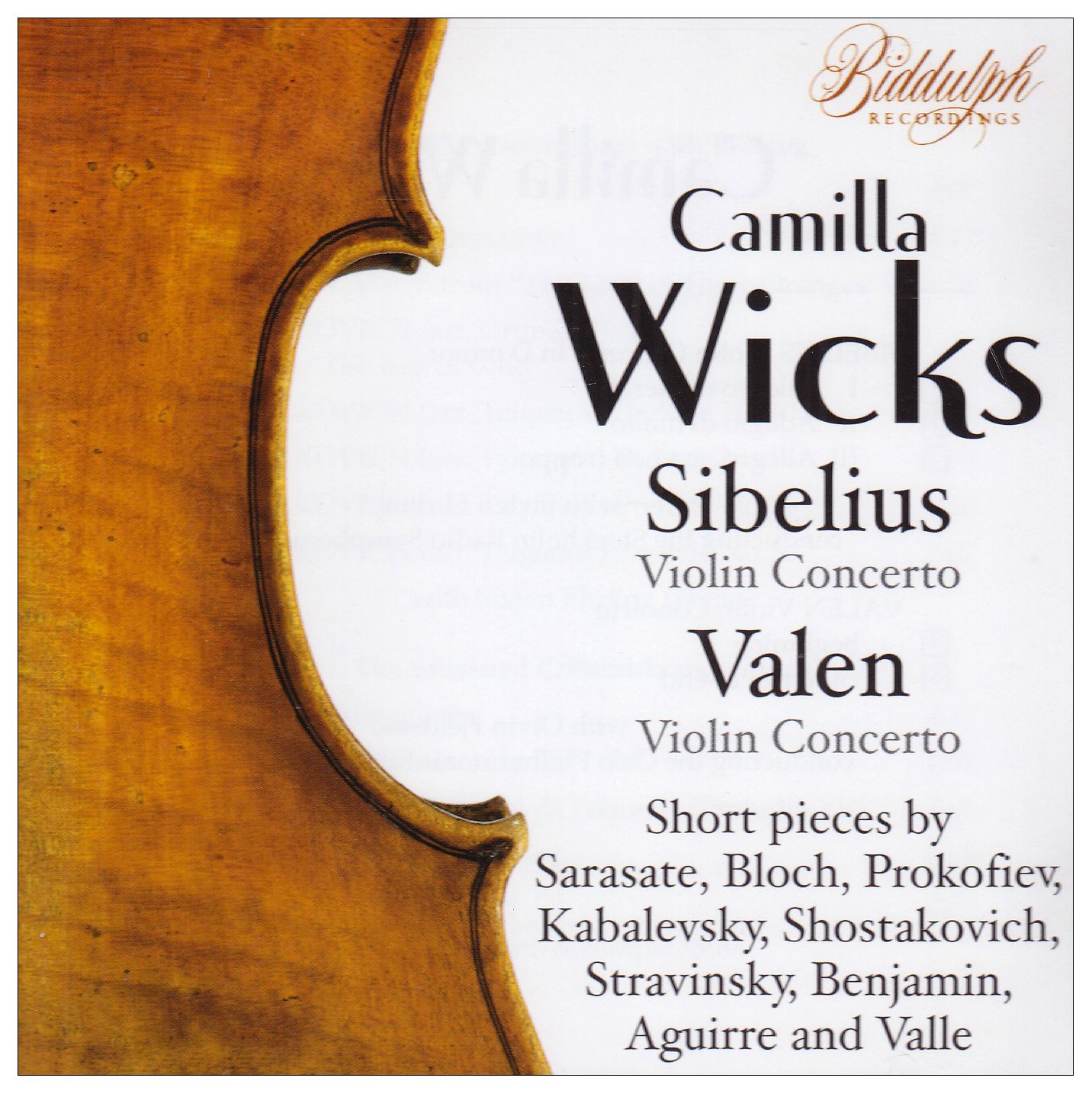

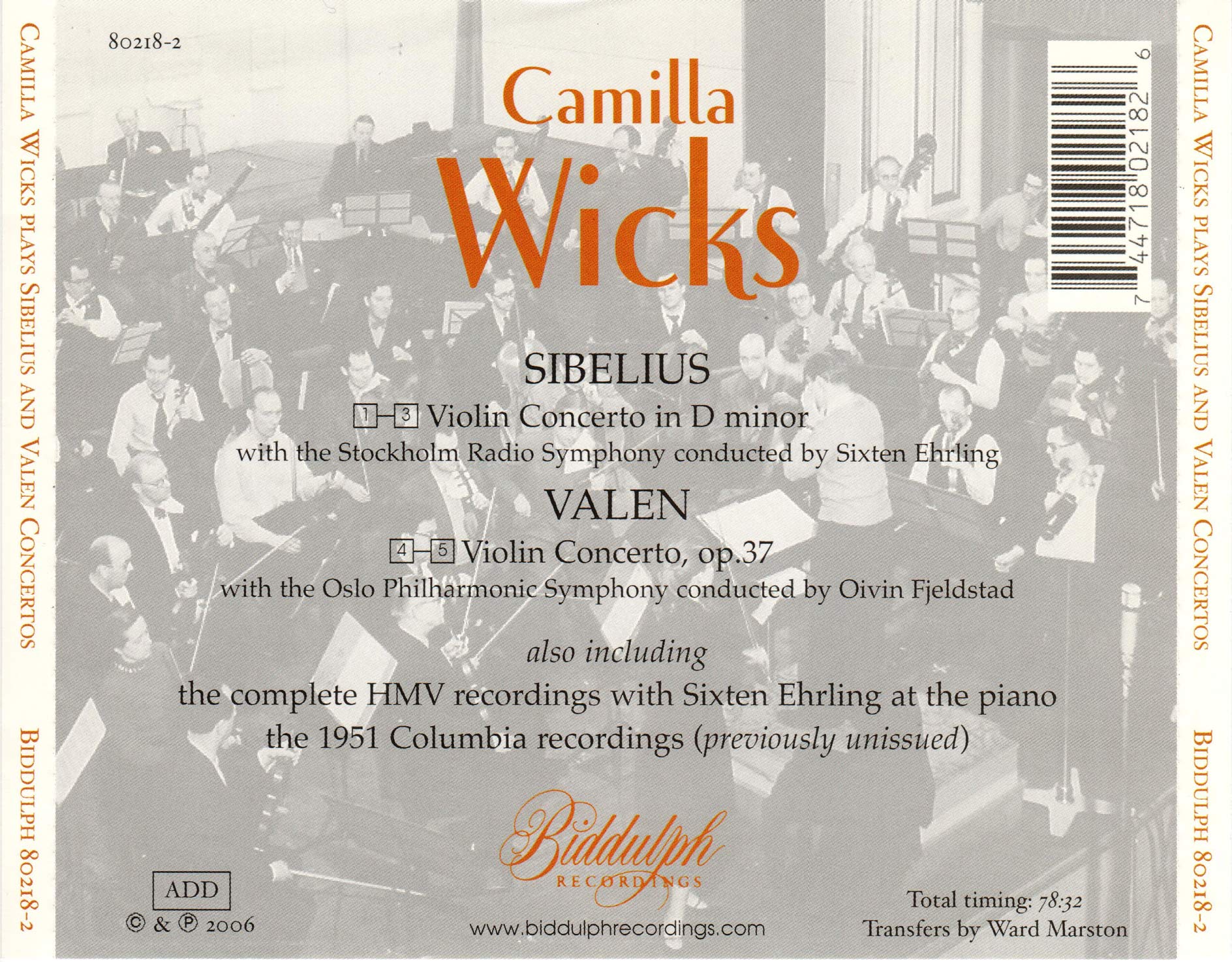

Presents – “CAMILLA WICKS - Sibelius, Valen Violin Concertos,” 2006

Short pieces HMV recordings and COLUMBIA unpublished recordings

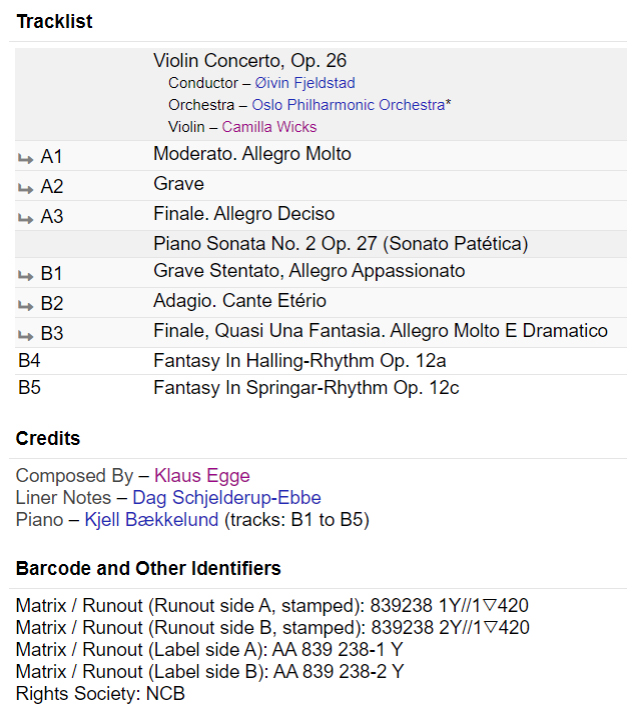

SIBELIUS: Violin Concerto in D Minor, Op. 47; VALEN: Violin Concerto; BLOCH: Nigun; KABALEVSKY: Improvisation; PROKOFIEV: March from The Love of 3 Oranges; SHOSTAKOVICH: Polka from The Age of Gold; Four Preludes (trans. Tziganov); SARASATE: Malaguena; AGUIRRE: Huella; VALLE: Ao pe da Foqueira; BENJAMIN: From San Domingo; STRAVINSKY: Pastorale – Camilla Wicks, violin/ Stockholm Radio-Symphony Orchestra/ Sixten Ehrling (Sibelius)/ Oslo Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra/ Oivin Fjeldstad (Valen)/ Sixten Ehrling, piano

Biddulph 80218-2 78:33

September 2006

By Jonathan Woolf

“Wicks’ Sibelius is the stuff of legend. Absence from the catalogues has only increased enthusiasm for its return. And all three of these recordings bring powerfully different approaches to bear; the cool reserve of Ignatius, the fiery, digging-into-the-string passion of Neveu and Wicks’s expressive but not overblown drama, architecturally magnificent in its completeness…

… “She had the advantage of collaboration with Sixten Ehrling, with whom she gave numerous concerts. Ehrling also proves an adept and highly accomplished pianist in their more intimate recordings here. In the Concerto, with Ward Marston’s transfers that seem successfully to have stabilised pitch problems on earlier issues, we can savour their commanding strengths. The opening is full of the subtlest tonal colour. Orchestral counter themes register with naturalness and surety. The agitated little string figures that are often subsumed are here present as part of the living fabric of the orchestral life force of the music. In the slow movement we find Wicks melancholic without ostentation – no overtly externalised finger position changes or timbral disparities. She remains unaffectedly direct, and strongly moving. Power and momentum characterise the finale. Wicks is no metronome, of course, and her rubati are finely judged and thoroughly convincing. Personalised phrasing adds immeasurably to a performance that remains as laudable now as the day it was recorded …”

Audiophile Audition

Jan 5, 2007

By Gary Lemco

“For many collectors, the inscription of the Sibelius Violin Concerto (18 February 1952) for Capitol Records by Camilla Wicks (b. 1926) and Sixten Ehrling remains one of the pinnacles of interpretation of this sinewy masterpiece. Two other women, Ginete Neveu and Guila Bustabo, achieved wonders with this Northern virtuoso vehicle, but the Wicks balanced virtuoso flair with a highly subjective warmth that ranked it among the great versions with Heifetz, Oistrakh, and young Isaac Stern.

Ehrling, too, was a natural Sibelius exponent, and his traversal of the Sibelius symphonies for Mercury Records needs to be restored to the active catalogue. After a hothouse Allegro moderato, the second movement, Adagio di molto, basks in a noble leisure that must be heard to define. Searching and poignant, the playing becomes feverish and yearning, with sighs and spasms of sound from the orchestra. The last movement is particularly earthy, the tympani parts complementing the violin’s demented shrieks in harmonics – truly a gavotte and rhumba for polar bears. A rhythmic freedom is no less perceptible that ingratiates this monumental performance, beautifully restored by Ward Marston.

The Concerto for Violin by Fartein Valen (rec. 1949) has its premier inscription with Oiven Fjeldstad. Cast in one large and one short movement, the piece has a rhapsodic feeling, but its syntax seems to owe much to the Violin Concerto by Alban Berg. Bartok may be an emotional kin. We tread through a dark, labyrinthine night, where the violin’s plaint has horn and woodwind wails or grumblings surrounding it. A degree of surface swish intrudes on the proceedings. The cadenza rises up in eerie harmonics over a bluesy horn call. A repeated figure gives the movement a through-composed quality. The huge sigh fades into the distance …”

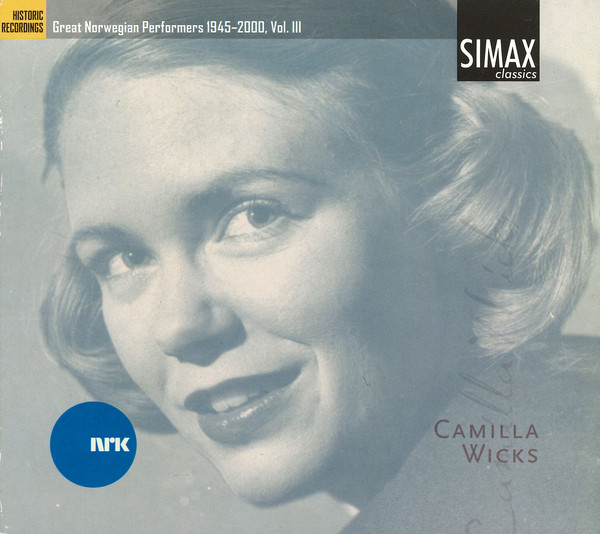

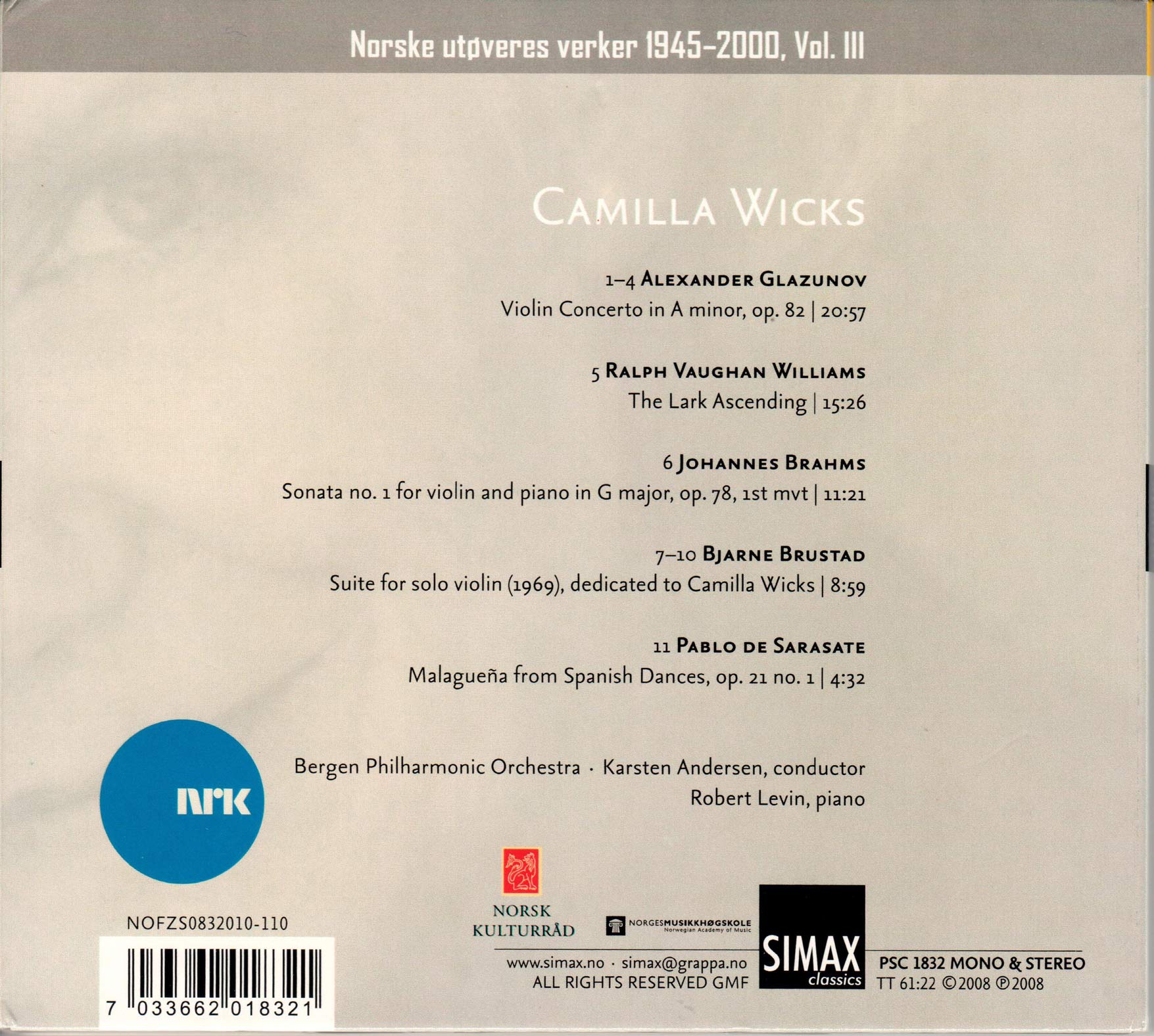

SIMAX - Great Norwegian Performers 1945-2000 - Camilla Wicks (2008)

2008, by Jonathan Woolf

“This is a disc that serves two invaluable functions. Firstly, rather more prosaically, it’s volume three in Simax’s Great Norwegian Performers 1945-2000 series. And secondly it stands as a royal salute to the great Camilla Wicks, in this, her eightieth year.

One of the best recent discs devoted to her was issued by Biddulph (see review) but there really can’t be enough. And this is where Simax is proving so invaluable, reminding us of Wicks’ importance as an artist. I have also reviewed an earlier Simax release of her Walton concerto and Bjarne Brustad’s Violin Concerto No. 4.

The Glazunov Concerto and The Lark Ascending derive from the same 1985 concert in which she was accompanied by the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra and Karsten Andersen. It would have been fascinating to have heard her Glazunov in the 1950s when she made her splendid recording of the Sibelius, now on Biddulph, when she was at her most fervent tonally. Her playing with the Bergen orchestra is nevertheless tremendously attractive; unforced, unpressed tempo-wise, taking twenty-one minutes in a work that, say, Heifetz and Milstein tended to dispatch in eighteen to eighteen and a half. This is playing that is subtly tinted and voiced though it can’t be denied that her vibrato has slackened. The highlight is probably the lightly elegant finale. As a footnote don’t be misled by the mis-tracking in the Andante; the return to the tempo primo seems to have confused someone which accounts for a separately tracked cadenza …”

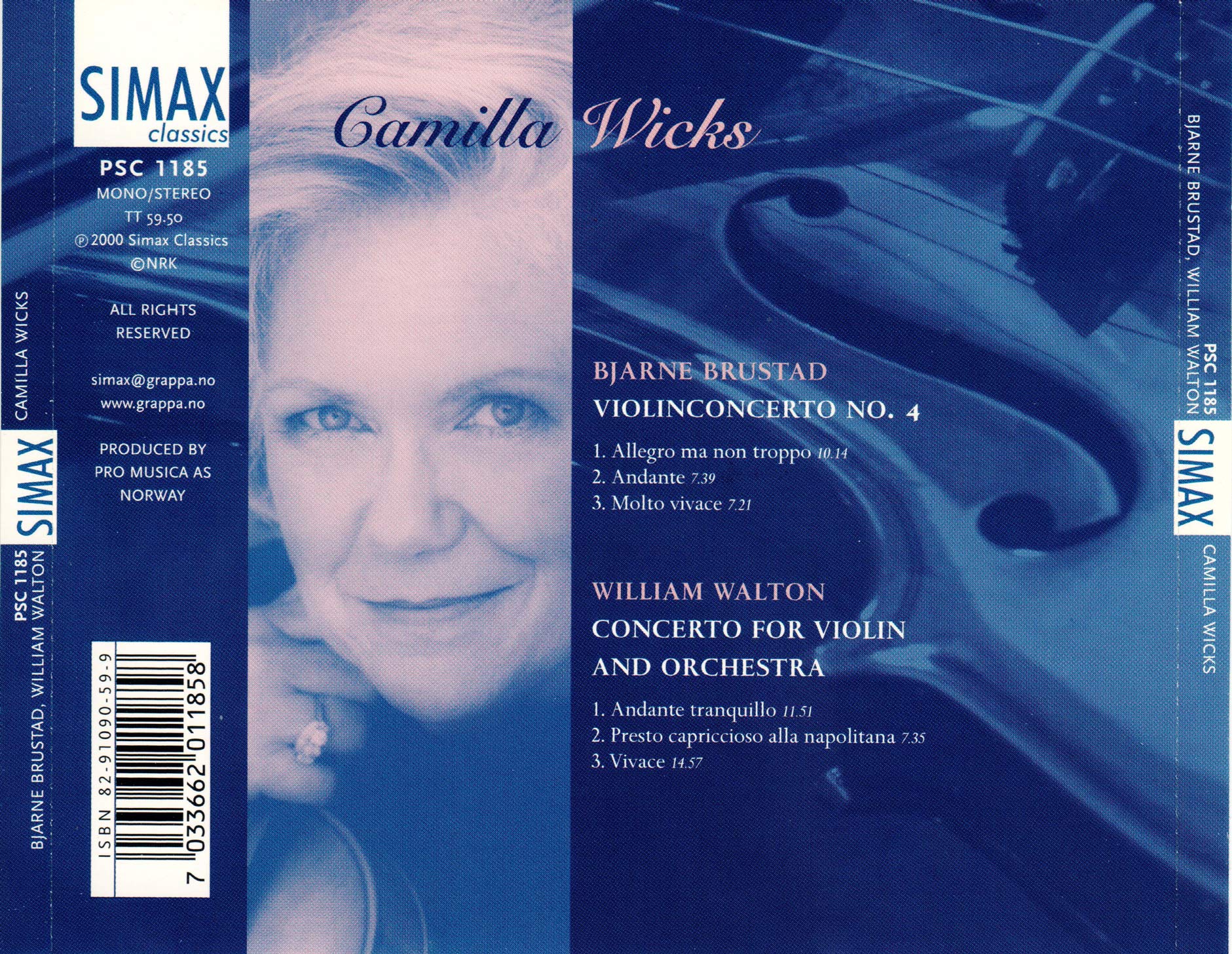

SIMAX Presents "Camilla Wicks - Brustad and Walton Concertos (2000)"

William WALTON (1902-1983)

Violin Concerto (1938-39) [33:22]

Bjarne BRUSTAD (1895-1978)

Violin Concerto No.4 (1963) [25:14]

Camilla Wicks (violin)

Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra/Juri Simonov (Walton), Herbert Blomstedt (Brustad)

rec. Oslo, live March 1968 (Brustad) and September 1985 (Walton)

SIMAX PSC1185 [59:50]

2000, by Jonathan Woolf

“In the light of Simax’s recent release devoted to Camilla Wicks – Glazunov and Vaughan Williams included (see review) – it’s appropriate to consider this earlier disc, one that pairs a Concerto of Bjarne Brustad, his Fourth, with Walton’s. They were recorded many years apart – the Brustad in 1968 and the Walton in 1985.

This is the most unusual performance of the Walton I’ve ever heard. It’s not simply a matter of speed, though it must be among the slowest on record, so much as the sense of tragedy that lies behind the playing. Firstly then it’s not unreasonable to consider the question of tempo relationships. The biggest discrepancy lies in the finale, which takes fifteen minutes. Great interpreters of the past – Heifetz, Senofsky and Francescatti, the first two with the composer conducting – agreed on 11:20 to 11:50. More to the point so did the composer. Wicks is also two minutes slower than Heifetz and Senofsky in the first movement and a minute and a half slower in the capricious central movement. The effect of this is to change almost completely the character of the music.

Wicks plays with refinement and control but the first movement transitions can sound excessive. Her silvery, no longer fiery, tone brings a certain aloofness, not the kind of luscious Mediterranean warmth that others seek. What she does find is an incipient vein of tragedy, of loss. The alla napolitana second movement is more Pierrot than devilish attaca. And the deliberate tread of the finale hardly honours the Vivace marking, though it too brings an unsettling sense of grievance and introspection. In all its a most diverting, really rather unsettling experience listening to Wicks’s Walton – rather like catching a usually avuncular friend weeping …”

2000 – “This disc highlights the virtuoso talents of violinist Camilla Wicks. Though Wicks was born in America and took her major music lessons here, she spent her busy adolescence back in Norway where, among other things, she became friends with Norwegian composer Bjarne Brustad. The Brunstad Violin Concerto No. 4, of 1963, is a freewheeling, energetic, and thoroughly Romantic affair with long cadenza sequences liberally placed throughout the three movements. Wicks’ performances here are virtually flawless. The same holds true for the Walton Concerto (1938/39): a performance of high contrast and real lyrical power. Its obviously the better-known work, but the Brustad could use more exposure.

Now the bad news: these are both concert performance recordings even though the booklet doesn’t say so. Between the movements of both works you can hear the orchestra shuffling their scores, the audience shifting in their seats, throats being cleared. Heavy applause follows the conclusion of both works. Also on the downside: the Brustad Violin Concerto is a mono recording. It’s hardly noticeable, but you can detect a slight flatness to the sound. However, to Wicks’ credit as a performer, one’s attention early on becomes focused on her artistic abilities, which were clearly exceptional. She holds her own against anyone in the Walton, and if you’re a fan of the violin and want to hear a decent, unknown concerto in the bargain, you’ll enjoy this.”

Profil Presents "Camilla Wicks Violin Concertos & Pieces (2018)"

Works include:

- Barber: Violin Concerto, Op. 14

- Beethoven: Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61

- Brahms: Hungarian Dances

- Brustad: Eventyr Suite

- Chopin: Nocturne No. 8 in D flat major, Op. 27 No. 2

- Chopin: Nocturne No. 20 in C sharp minor, Op. post.

- Kreisler: Tambourin Chinois, Op. 3

- Mendelssohn: Gesange (6), Op. 34

- Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64

- Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64

- Sarasate: Danzas Española, Op. 21

- Sarasate: Introduction and Tarantella, Op. 43

- Scarlatescu: Bagatelle

- Schubert: Ave Maria, D839

- Sibelius: Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 47

- Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35

- Wieniawski: Violin Concerto No. 1 in F sharp minor, Op. 14

- Wieniawski: Violin Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 22

Note: This album appeared in 2018. No one in Wicks’ family was contacted by this production company.